11 Contributing to CADP

11.1 Our Kanban process

We follow a Kanban process that Brian perfected over six years. The approach is designed to minimize coordination time and miscommunication in a distributed and asynchronous collaboration environment. The process was successful during COVID while managing a remote team in the Philippines.

11.1.1 Lean production

Kanban literally means “sign board” in Japanese. Its history is steeped in lean production and like most of lean production, its genesis occurred at Toyota. To really understand the Kanban approach it’s necessary to understand a bit about lean production, and in particular the concept of efficiency and waste. Our starting assumption is that we want to optimize processes so they are maximally efficient. What does it mean to be efficient? One definition focuses on what it isn’t or doesn’t have, which is waste. Lean production aims to remove as much waste from a process as possible. The more waste is removed, the more efficient the process.

Lean production defines seven wastes, often abbreviated as TIMWOOD. These are

- transportation: moving parts, inventory from one location to another. Long distances or small capacities result in waiting and expose materials to transportation risk

- inventory: storage of parts and goods. Inventory can get damaged or obsolete, leading to wasted resources

- movement: physical movement of the body, like walking to a copy machine. Movement expends energy and consumes time. Less physical movement for repeated tasks saves time

- waiting: idle time waiting on someone else (or a dependency). Time is money; you’re typically paying someone to do nothing

- over production: creating more than necessary. Excess becomes inventory, so money and time is spent producing things that don’t provide value

- over processing: doing more than necessary (e.g., over-thinking, over-designing). Ignoring the Pareto principle and the law of diminishing returns leads to spending a lot of time to achieve little incremental improvement

- defects: manufacturing errors, communication errors.

While the original context was physical production, the seven wastes of lean transfer remarkably well to business processes, software development, and even AI systems. It’s particularly important for data and data science:

- transportation: moving data from one server to another. Data transfer rates and bandwidth limit the rate of delivery.

- inventory: storage of data and artifacts. Like inventory, data can become obsolete, and it costs money to store it.

- movement: manual steps in processes. The more steps with human involvement, the longer it takes to accomplish and the more error prone they are

- waiting: for data to download/upload, model to finish running, coordination

- over production: creating too much data

- over processing: over-designing a process, over-fitting a model

- defects: data errors, model errors, process errors, communication errors

11.1.2 Loose coupling and asynchronous communication

The original kanbans were pieces of paper that were placed at the bottom of a parts bin. This sign board communicated to the consumer of those parts that it was time to get more parts. They would take the card to the producer of those parts so they could begin making more.

Kanban is thus an integral part of just-in-time (JIT) production, where said production is driven by a pull process (initiated by demand). The genius of kanban is that each producer operates independently and coordination is asynchronous. An effective kanban process doesn’t require a lot of meetings nor does it require a lot of coordination. All it requires is an understanding of and adherence to the process.

11.1.3 Kanban for project management

Outside of a physical production process, a centralized kanban board can mediate communication between relevant parties. Each person fulfills a particular role and has certain actions they can take. Note that a person can fulfill multiple roles. For software, the roles can include:

- product owner: responsible for defining requirements and setting priorities

- individual contributor: responsible for implementing requirements

- tester: responsible for testing implementations and documenting errors

- deployer: responsible for deploying code to different environments

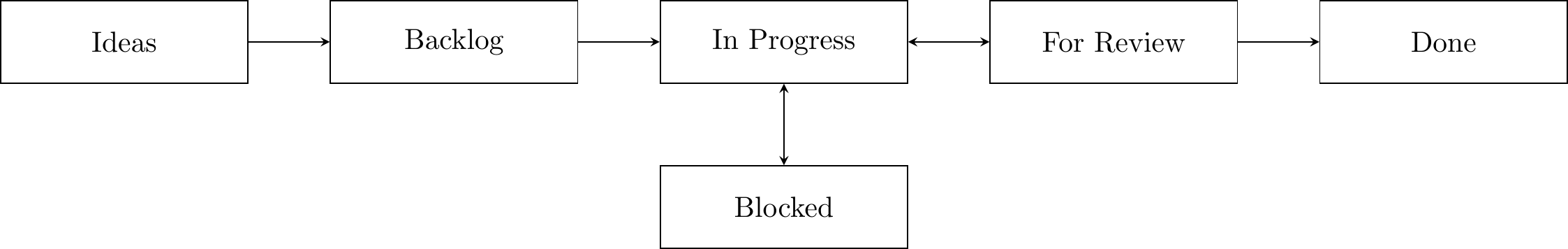

The kanban itself is simply a set of columns in a particular order. The columns hold cards or stories that define work to be done. Each column represents the state of the cards within the column. While any columns are allowed, I use a standard set. Figure 11.1 shows the relationship between the column states and how cards can move between those states.

Figure 11.1: A state diagram representing where cards can move from each column. The starting state is always Ideas, and the end state is always Done.

Here is a description of each column state:

- ideas: represents a proposed work item. Anyone can add a card to ideas, but only the product owner can move a card from ideas into the backlog.

- backlog: represents prioritized work that has (sufficiently) complete requirements. This column acts as a queue.

- in progress: represents work that is actively being worked on. Individual contributors move cards from the Backlog into In Progress and assign themselves to the card. To minimize ambiguity, there should be one card owner that is ultimately responsible for the completion of the card. Typically people add an update each day they work on the card. This is critical as it provides visibility into the process and eliminates the need for status updates or in-person meetings!

- blocked: represents a stuck state, where an external situation is preventing forward progress. Card owners move cards from In Progress to Blocked and must include an explanation of the blocker. The card owner is responsible for coordinating the solution to unblock the card. Once a card is unblocked, the card owner moves the card back to In Progress.

- for review: when work is finished on a card (code complete), the card owner moves the card to For Review. She must tag a reviewer and follow up to ensure the card is reviewed in a timely manner. Depending on the team, a reviewer can be another individual contributor or the product owner. If there is significant work to be done for a review, the card owner may move the card back to In Progress. For simple issues, it can remain in For Review.

- done: work that has gotten a successful review is moved here by the card owner. It is up to the team to agree on the definition of “done”. This state can signify code has been merged to the master branch, deployed into a particular environment, or something else.

11.1.4 The need for discipline

Kanban works because of the visual signaling and the clear rules for each role. When everyone adheres to the rules of the board, communication errors are reduced since people have the same interpretation of the status of a card. It’s similar to driving. The rules of a four-way stop sign are clear. When everyone follows the rules, the flow is efficient and there are minimal delays or accidents. But the moment one person ignores the rules, then the expectation changes. It is no longer clear what the protocol is, and accidents can happen.

11.2 Micropython

11.2.1 UNIX port

For development, using the UNIX port of Micropython can be helpful.

Install from source:

$ sudo apt-get update && sudo apt-get install libffi-dev

$ git clone git@github.com:micropython/micropython.git

$ cd ../ports/unix

$ make submodules

$ makeor install an old (stable) version via sudo apt-get install micropython.

After this, Micropython can now be used in the terminal by using the

command micropython.

It can also run a python file via micopython foo.py.